The melting of sea ice in Greenland is revealing a new land border, altering the physical, ecological and strategic balance of the Arctic. This rapid glacial retreat is exposing unstable coastlines and unknown islands, and fuelling territorial disputes in a region increasingly coveted for its resources and maritime access.

By Laurie Henry

Global warming is not only changing temperatures, it is literally redrawing the world map. In the Arctic, rapidly melting glaciers are transforming landscapes. This phenomenon is most spectacular in Greenland, where 1,620 kilometres of coastline emerged between 2000 and 2020 as a result of glacial retreat. A new publication in the journal Nature Climate Change highlights the concrete consequences of a planet that is warming too quickly: a reshaped Arctic coastline, weakened ecosystems and suddenly available territories, fuelling greed and uncertainty.

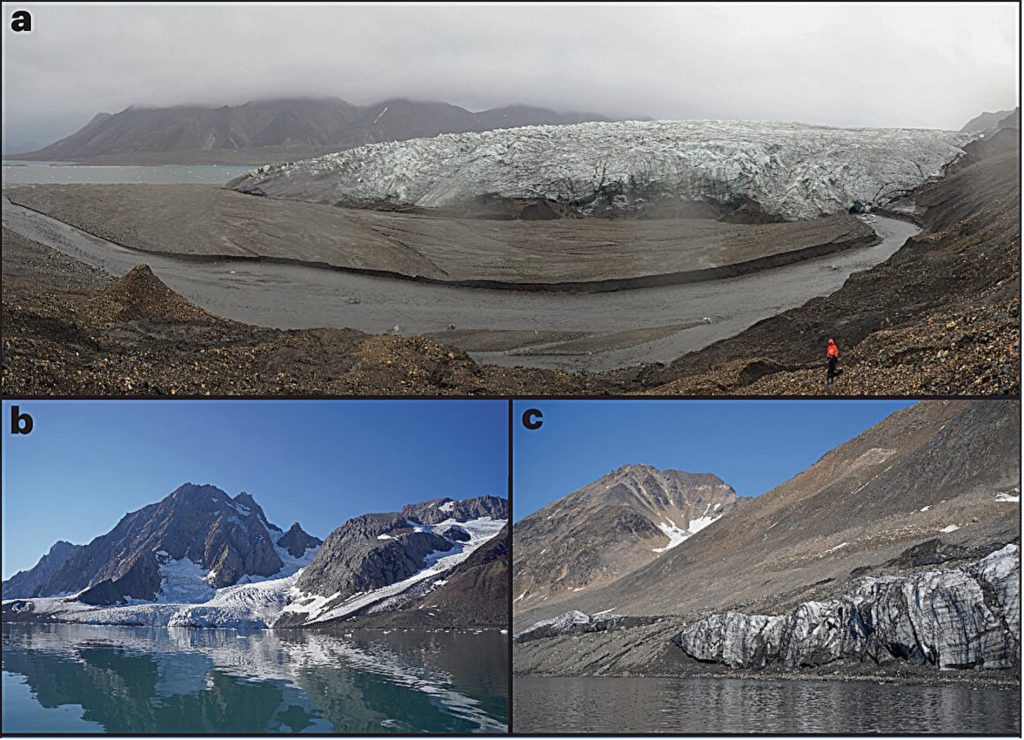

Diversity of new coastlines after glacier retreat. © Kavan J., et al., 2025

Rapid transformation of the Arctic coastline

The work is based on cross-referencing satellite data and geological observations. Satellite images from the Sentinel-2, Landsat-7 and Sentinel-1 missions are carefully analysed to compare the positions of glacier fronts between 2000 and 2020. A total of 3,217 coastal sections associated with glaciers flowing into the sea were examined. The researchers were thus able to accurately delineate the newly exposed and disappeared portions of the coastline, taking into account uncertainties related to the spatial resolution of 10 to 30 metres depending on the sensors used.

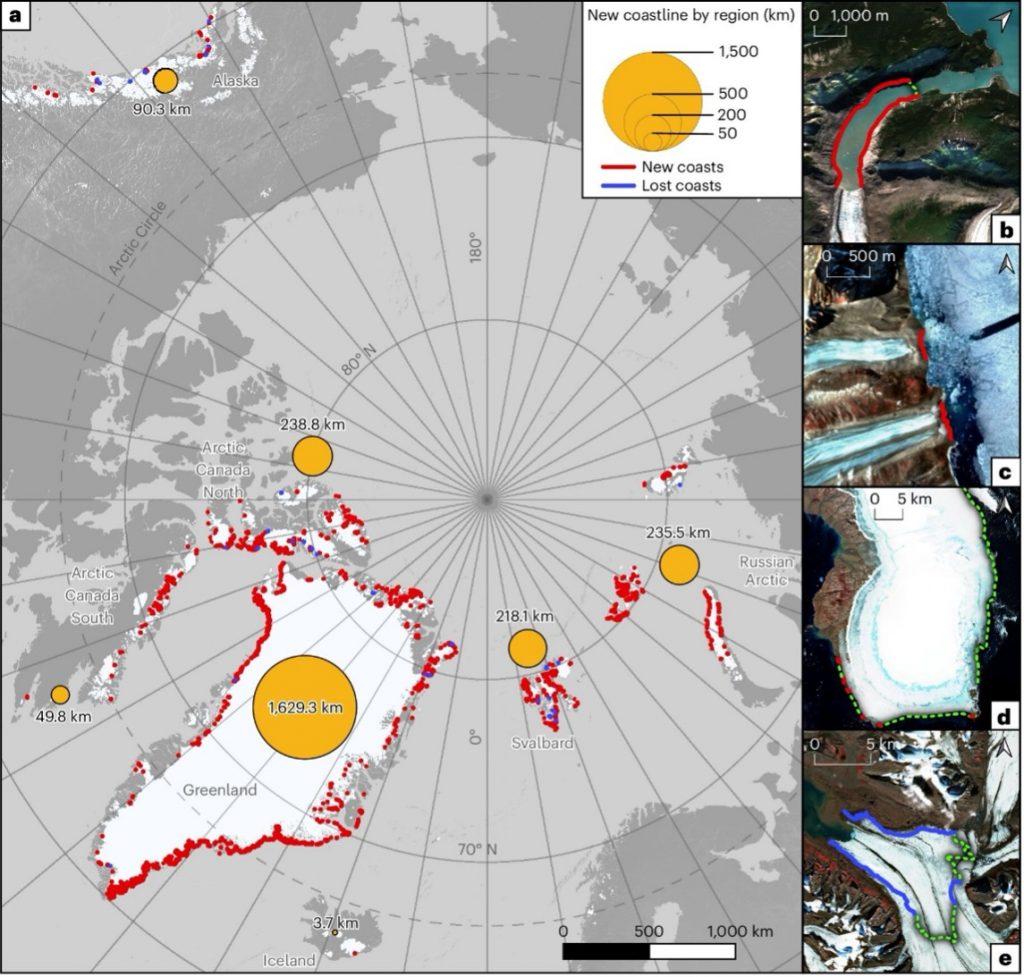

The results are unequivocal: 2,466 kilometres of new coastline have emerged across the Arctic, including 1,620 kilometres, or two-thirds, in Greenland. This proportion can be explained by the massive extent of the Greenland ice sheet and the configuration of its fjords. The Zachariae Isstrom glacier in north-eastern Greenland has seen its glacier tongues melt, revealing more than 81 kilometres of coastline, a record for the northern hemisphere.

The study also highlights the heterogeneity of the effects of glacier retreat. The metric used to quantify the effectiveness of retreat in terms of coastline formation – known as the NC–RA ratio for new coastline to retreat area – reveals significant regional contrasts. For example, Alaska and the southern Canadian Arctic have high NC–RA values, with modest surface glaciers retreating into narrow valleys, which multiplies the length of the newly formed coastline. At the same time, the dominant presence of floating platforms surrounded by open sea in regions such as the Franz Josef Land archipelago severely limits the formation of solid shorelines, and even significant glacial retreat leaves few traces that can be mapped.

Spatial distribution and examples of new and disappeared coastlines in the Arctic from 2000 to 2020. © Kavan J., et al., 2025

Finally, scientists note that this process is not linear. Of the 1,704 glaciers studied, 85% have receded, but only 71% have generated new coastlines. In some cases, the retreat occurs without exposing adjacent land, particularly when floating glaciers lose lateral contact with the mainland.

Changing landscapes and exposed geology

The study reveals that the coastlines exposed by the retreat of marine glaciers are not uniform surfaces. They form paraglacial landscapes, a term used to describe areas newly freed from ice and still strongly influenced by their glacial heritage.

These environments are characterised by high geomorphological instability. They include moraines (accumulations of rock debris transported and deposited by glaciers), eskers (elongated ridges formed by subglacial rivers), deltas formed by glacial river deposits, and outcrops of metamorphic rocks polished by ice friction.

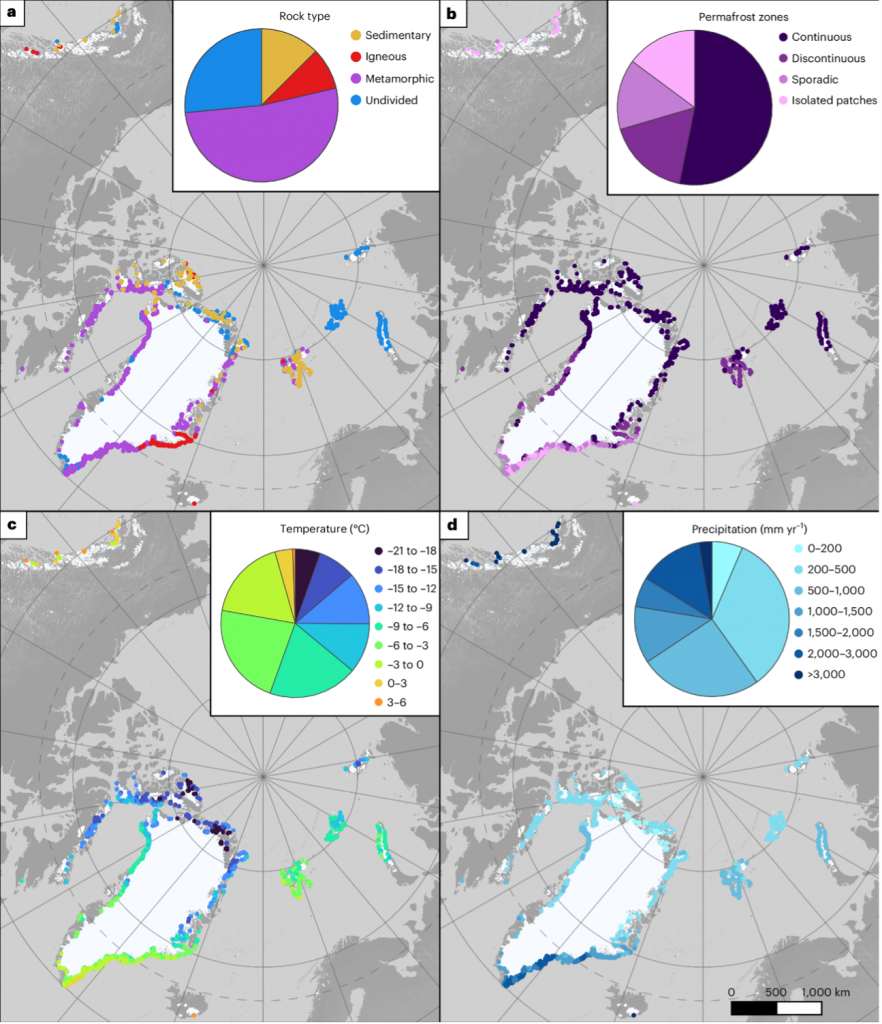

The researchers divided the 2,466 km of new coastline into 500-metre sections in order to characterise its geological composition and thermal conditions in detail. This analysis shows that most of these shorelines are located in areas of continuous permafrost (soil that is permanently frozen for at least two consecutive years, editor’s note), which in the Far North can reach depths of several hundred metres. The areas concerned have average annual temperatures of between -12°C and -20°C, which makes the permafrost refilling process very slow after glacial retreat.

Geological and climatic summaries of newly emerged coastlines.© Kavan J., et al., 2025The time required for the ground to refreeze is estimated at a minimum of two years. This creates a critical period during which unconsolidated materials—sand, gravel, silt—are particularly susceptible to erosion. This fragility is accentuated in areas composed of sedimentary rocks, which are softer and more friable than metamorphic or igneous (volcanic) rocks. In Svalbard and eastern Greenland, for example, where sedimentary outcrops dominate, coastal erosion processes are therefore likely to be particularly rapid and difficult to anticipate.

Satellite images have also made it possible to correlate the geological nature of exposed terrain with its dynamic behaviour. Researchers have found, for example, that coasts resting on metamorphic rocks, which are harder and more stable, evolve slowly. In contrast, those composed of loose materials, such as glacial sediments, undergo rapid transformations. This process is amplified not only by wind and waves, but also by the melting of residual ice blocks left behind by the glacier. Although the main glacier has receded, isolated fragments of ice often remain, buried under moraines or on the surface. Their rapid melting weakens the newly exposed soil, promoting erosion and coastal reconfiguration.

New islands and potential tensions

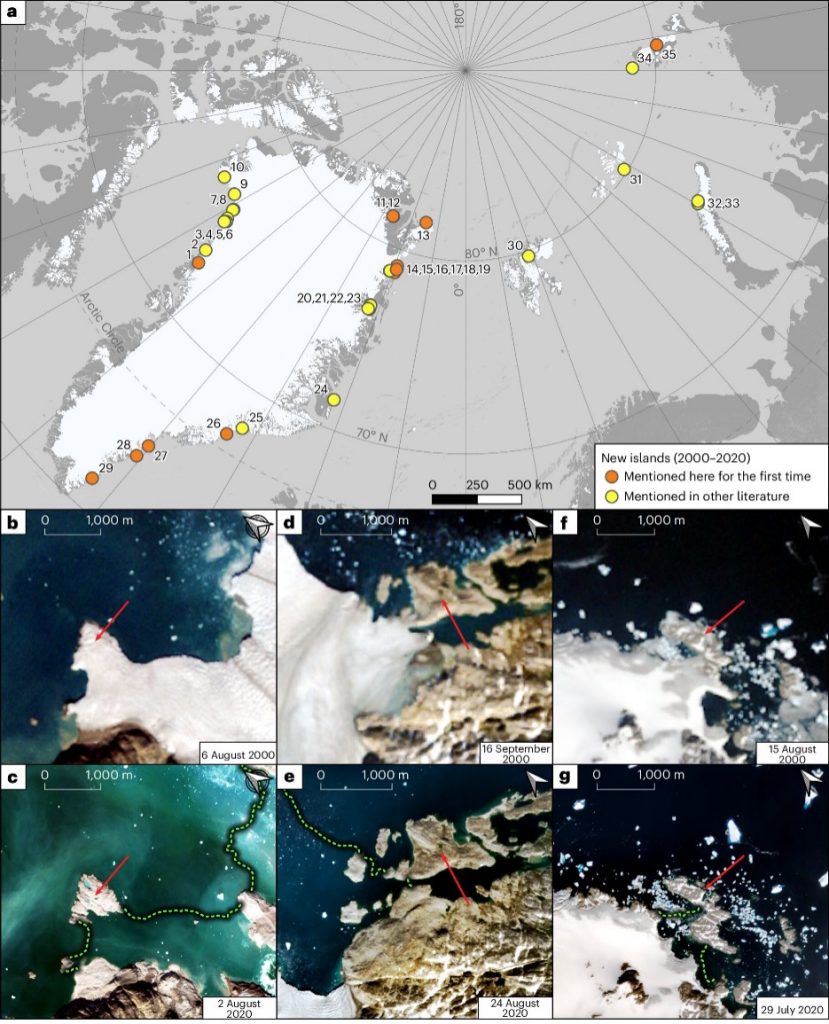

Glacial retreat is also causing previously unknown or inaccessible islands to emerge. Researchers have identified 35 new islands with an area greater than 0.5 km², a threshold chosen to exclude rock outcrops that are too small or seasonal and to ensure the cartographic stability of the entities surveyed.

Of these 35 islands, 29 are located in Greenland and 13 were not mentioned on any previous topographical maps. However, some of these islands were visible in surveys conducted in the 1960s, before they were covered by glacial advances, particularly during periods of temporary cooling. The scientists compared the positions of the ice fronts between 2000 and 2020 by superimposing historical data and old maps and then confirming the topographical isolation of the islands using altitude models derived from satellite imagery.

Map and examples of new islands detected between 2000 and 2020 in the Arctic. © Kavan J., et al., 2025

Beyond scientific curiosity, these islands raise the legal question of ownership, since under international law, unclaimed land above sea level may, under certain conditions, be subject to territorial claims. The current absence of claims to these new islands therefore opens up a vacuum with significant geopolitical implications. In a rapidly changing Arctic region, where potential resources are already attracting interest, this situation could trigger major international rivalries.

The geopolitical implications are far from theoretical, as powers such as Russia, Canada and the United States have been strengthening their military and diplomatic presence in the Arctic for several years. The Trump administration’s interest in a possible purchase of Greenland, officially for strategic and security reasons, is part of this dynamic. In a context where the ice is melting faster than international law can adapt, the redefinition of physical borders is accompanied by a reshaping of international power relations.

A new geography of risk in a warming world

The rapid emergence of new coastlines in Greenland is accompanied by concrete risks, both for ecosystems and human activities.

Areas newly freed from ice are increasingly unstable. They are exposed to hazards such as tsunamis caused by landslides, waves generated by icebergs capsizing, and moraine collapses. These phenomena, which can sometimes be violent, threaten local populations as well as certain infrastructure linked to polar tourism, some of which is located close to glacier fronts.

At the same time, the reduction in the number of floating glaciers could improve navigation safety by limiting iceberg drift. This change opens up the prospect of new routes becoming accessible as the ice melts. From an ecological point of view, the newly exposed shorelines are virgin environments, conducive to the establishment of new forms of life. However, these habitats are fragile and their long-term stability will depend on many factors, including soil refreezing, sediment dynamics and anthropogenic pressures.

Scientists stress the importance of continuous monitoring of these changes. Glacier retreat is not limited to a loss of glacier mass; it redefines the interfaces between land, sea and atmosphere, with cascading effects. On a regional scale, these changes are redrawing the Arctic margins while reflecting the intensity of the upheavals underway in polar regions worldwide. The Arctic is undoubtedly a key study area for understanding the structural impacts of climate change on territories, resources and environmental balances.

Source : Kavan, J., Szczypińska, M., Kochtitzky, W. et al. “New coasts emerging from the retreat of Northern Hemisphere marine-terminating glaciers in the twenty-first century”. Nat. Clim. Chang. 15, 528–537 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-025-02282-5